Biologist Jerry Cole installs an ARU at a target area for bird monitoring (photo courtesy of The Institute for Bird Populations).

Steven Albert and Jerry Cole, The Institute for Bird Populations

The digital revolution has greatly benefitted the study of birds. Apps such as eBird and Merlin are in wide use both recreationally and scientifically, and the miniaturization of electronics has made tracking birds across the globe—often in real time—relatively easy and cheap.

One type of monitoring that has recently grown in sophistication and ease of use is acoustic monitoring via Autonomous Recording Units (ARUs). ARUs are recording devices that can be placed in weatherized cases, deployed virtually anywhere, and set to start and stop recording at pre-programmed times. The recordings are stored on SD cards and later analyzed by sophisticated computer programs that have been trained using libraries of thousands of bird songs, calls, and other sounds, to create a list of species detected.

Remote sites like this habitat in California’s Mohave Desert are ideal for ARU use (photo courtesy of USFWS).

The Institute for Bird Populations (IBP) is currently working with the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) at remote desert sites in the SJV region of southeastern California to monitor the bird communities for rare and sensitive species, and to document the timing of use by migratory and resident birds.

In several studies, ARUs have shown comparable detection ability to human observers, at least when deployed over long-time intervals. Of course, the units cannot detect birds that don’t vocalize, but they nevertheless provide many benefits for monitoring and research. For example, they are ideal for organizations with small staffs that have remote locations to survey. Deployed in arrays of multiple units, ARUs can catch the “dawn chorus” when birds are most vocally active at dozens of locations simultaneously.

Individual ARUs can record for hundreds or thousands of hours during a season, which may be especially useful for detecting species that have low detection probability during typically short-duration human surveys, or that might be sensitive to human visitation. For example, IBP is also working with the BLM to monitor Sage-Grouse leks, to determine which are active, and for how long (Sage-Grouse are vulnerable to human disturbance during this crucial life history stage).

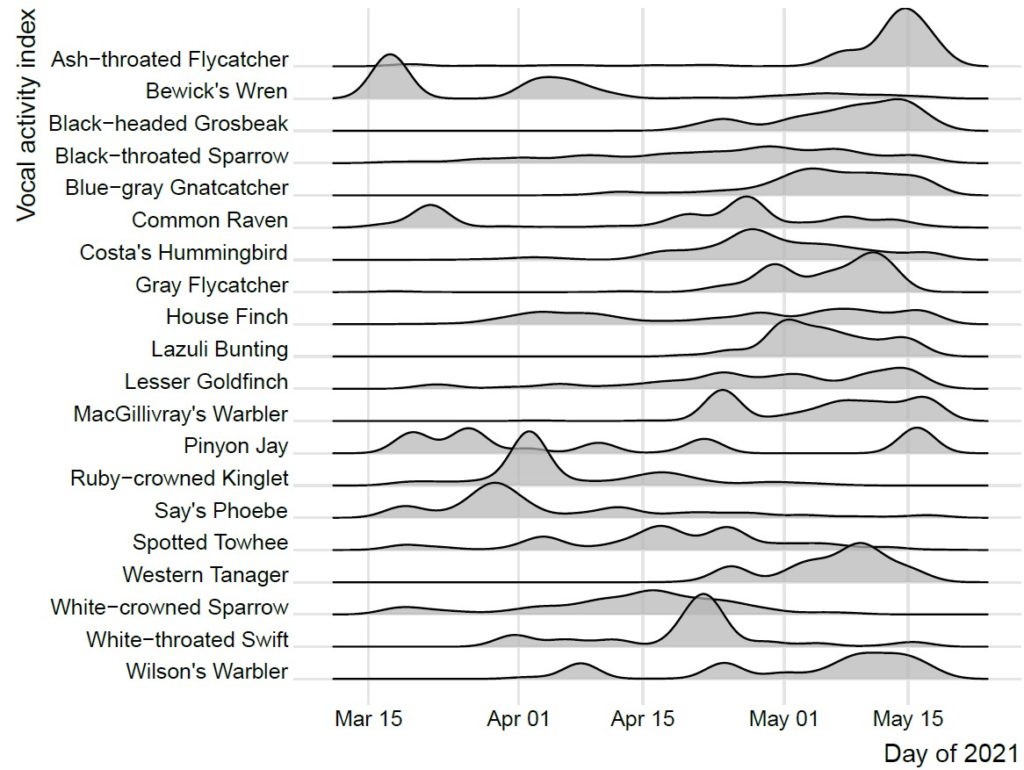

ARUs can provide insight into bird activity that are impossible from a small number of human visits. For example, the timing of a birds’ annual cycles–migration, breeding, fledging young, etc.–vary by species. ARUs have the ability to detect peaks and valleys of vocal activity for a multitude of species, which might be otherwise missed (see figure below). Another benefit is that ARUs create a permanent record of what was vocalizing on a given day, preserving information for future scientific inquiries.

English

English  Español

Español