Lindsey Gottwig with an adult Yuma Ridgway’s Rail at Arlington Wildlife Area, Arizona. The solar satellite transmitter sends location data every 2 days to help track the movements of this rail. Indeed, this very rail is now wintering in a mangrove forest near Guaymas, Sonora, Mexico (photo by Daniel Hite).

By Eamon Harrity, Idaho Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Unit, University of Idaho and Dr. Courtney J. Conway, USGS Idaho Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Unit, University of Idaho

Wetlands may seem unpleasant to many people– with good reason. Wetlands can be muddy, buggy, smelly, and full of impenetrable vegetation. But, to the rare and secretive Yuma Ridgway’s Rail, these unpleasant wetlands are home. We followed this elusive bird into the muddy, buggy, and smelly marshes of the southwestern U.S. during the past 4 summers and the results have been fascinating.

Yuma Ridgway’s Rails inhabit emergent marshes along the Lower Colorado River, Lower Gila River, and Salton Sea. These birds are supremely adapted to their marshy environs: strong legs and large feet help them maneuver through the dense marsh vegetation, long beaks allow them to capture prey in mud and shallow waters, and mottled brown plumage offers excellent camouflage. Unfortunately, these secretive birds are threatened by habitat loss due to land use changes, water diversions, and river regulations throughout the southwestern U.S. Indeed, Yuma Ridgway’s Rails have been listed as federally endangered for more than 50 years, and habitat loss is considered a primary challenge to successful species recovery. While land management agencies protect and manage marshes to maintain quality habitat for the rail, a novel threat to the rail’s recovery may be emerging far removed from the marshes.

Eamon Harrity and Maddie Ybarra carefully attach a solar satellite transmitter (Lotek Wireless, Inc) to track the movements of this Yuma Ridgway’s Rail (Photo by Peter Pearsall).

Yuma Ridgway’s Rails are considered largely non-migratory because telemetry studies in the 1980s and 1990s reported most rails remained in small home ranges all year. Experts were startled when multiple Yuma Ridgway’s Rail carcasses were found at solar facilities far from any wetlands in 2013-14. Unfortunately, avian deaths at solar facilities are well documented (tens of thousands of birds die annually at solar facilities in the southwest), but solar facilities in the desert were not considered a threat to Yuma Ridgway’s Rails because the evidence suggested these rails rarely left their marshy homes. The reports of these rail deaths spurred conservation agencies, including the Sonoran Joint Venture, into action, and launched a project with Dr. Courtney J. Conway and Eamon Harrity at the University of Idaho (with funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, and Bureau of Land Management) to investigate the long-distance movement behaviors of these rails.

To better understand their long-distance movements, we capture and outfit rails with satellite transmitters by carefully tying a backpack-style harness to hold the transmitter in place without impeding locomotion. The transmitters are solar powered and exceptionally lightweight. The insights we have gained from these transmitters have been breathtaking. Not only are these rails leaving the marshes regularly, they are migrating to coastal areas in Mexico with long and sustained flights over open desert terrain.

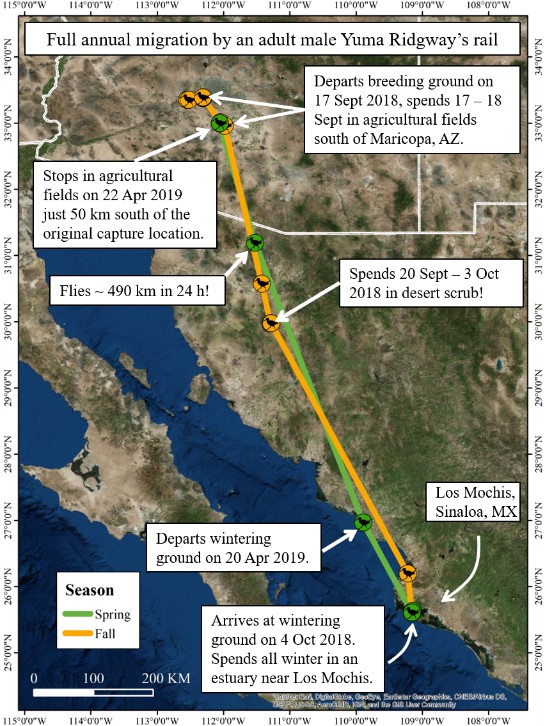

Full annual migration completed by an adult Yuma Ridgway’s rail in 2018-2019 (map by Eamon Harrity).

A male Yuma Ridgway’s Rail we captured near Phoenix, AZ completed one of the most remarkable journeys yet documented. We captured the rail at Base & Meridian Wildlife Area where it maintained a relatively small home range all summer. In mid-September, the rail flew ~450 km in a few days to a small patch of desert scrub in Sonora, Mexico. We monitored the movements in disbelief as this marsh bird spent 10 days in desert scrub. After apparently refueling, the rail moved to a mangrove forest near Los Mochis, Mexico– nearly 1000 km south of the summer home range. The rail moved back to the Lower Gila River in mid-April, thus completing the first migration ever documented in this species! We have since documented rails migrating to coastal estuaries and mangrove forests near Puerto Peñasco, Bahía Kino, and Los Mochis, Mexico. We’re excited to document movements of additional rails through our monitoring this fall.

We are beginning to understand the phenology and movement corridors of migration of Yuma Ridgway’s Rails. Such information will help ensure that solar development and rails can coexist in the desert southwest. Moreover, we now know that these rails are moving regularly from the U.S. to Mexico, and efforts to conserve this species must be coordinated between both countries. To this end, we are collaborating with SJV partner Pronatura Noroeste to further understand the movements of these rails between the U.S. and Mexico. We attached transmitters to rails in the Colorado River Delta this summer, and plan to expand our efforts to the west coast of the Gulf of California (i.e., where many of the rails overwinter) in January.

Successful conservation and recovery of a species requires an understanding of the full annual life cycle of the species. Our research efforts and collaborations are carrying us towards just such an understanding for Yuma Ridgway’s Rails, and will hopefully ensure that the muddy, buggy, and smelly marshes of the southwest continue to support populations this remarkable marsh bird.

English

English  Español

Español