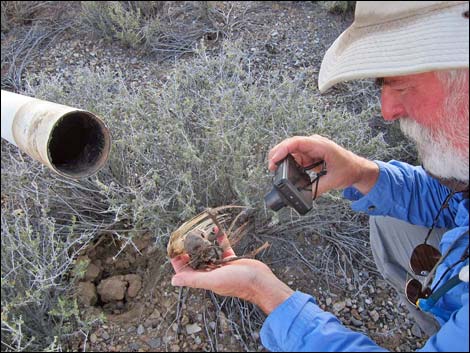

An owl, one of many cavity nesting birds species is caught in a mining claim marker (photo courtesy of Jim Boone).

Mining claim markers like this one may stand silently for decades, capturing and killing wildlife (photo courtesy of Jim Boone).

By Emily Clark

Mining claim markers that use open pipes are a deadly threat to birds and wildlife. In the western United States, the large amount of public lands make this a particularly important issue. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is responsible for the stewardship of the majority of these public lands. Federal law governing locatable minerals allows citizens to explore, discover, and purchase mineral deposits on public lands. Prospectors historically used uncapped PVC pipes to mark the four boundaries of their claims. Wildlife enters the hole of the open pipes looking for food, shelter, or a nesting cavity. Unfortunately, the smooth walls of the pipes prevent wildlife from climbing out, leading to dehydration, starvation, and death. Open pipes kill millions of birds and other wildlife annually, an easily preventable source of mortality. To give you an idea of how broad spread this issue is, in 2015, there were 3.5 million mining claims nationwide on BLM managed land; Nevada had the most with over 1.1 million claims registered. If even half of those claims use uncapped pipes as markers, that is over a million unintentional traps, waiting to kill birds and other wildlife.

Two live side-blotched lizards that were rescued from a pipe, and one that didn’t survive (photo courtesy of Jim Boone).

Nevada is leading the charge to tackle this issue. A 1993 state law prohibited the installation of uncapped pipes for marking mining claim boundaries, but it did not require the removal of old markers, nor did it require monitoring of capped pipes once they are installed. Due to wear from the harsh desert weather, estimates suggest that caps from about half of the pipes that were covered when installed have since fallen off, posing a threat to wildlife. Pete Bradley and Christy Klinger, wildlife biologists with the Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW), have been spearheading an effort to both remove abandoned pipes and prevent further death, as well as documenting the impact these pipes have on wildlife. They realized that the law did not go far enough, and worked with leaders from the local Audubon Society to draft new legislation, which was passed in 2009. The new law requires the use of solid markers (not capped hollow pipes), invalidates any mining claim marked with an open pipe, and most importantly, includes a citizen provision that allows anyone to pull out open claim markers and lay them on the ground (effective in 2011). Unfortunately, most states do not have these provisions, where open PVC pipe claims are still legal.

Mark Slaughter is the Natural Resource Supervisor for the Southern Nevada District of the BLM. He first became aware of the problem during a field trip in 2008 to remove pipes with Christy Klinger, in which they found about 25 dead birds in one pipe alone. Since that time, he has been passionate about the issue, and committed his district to removing the abandoned pipes spread across the 3.6 million acres they manage, which is no easy feat.

“Once we got started, the scope of it was a little more overwhelming that we thought. We had to take a step back and come up with a long-term plan,” explained Slaughter. Part of that plan involved using helicopters to conduct aerial surveys for mining claims. They developed topographic maps showing the areas with the highest densities, which they tackled first.

“Out of the roughly 1 million mining claims in Nevada, only 200,000 are active, while about 800,000 are abandoned,” Slaughter stated.

In Slaughter’s words, it takes a village to remove the abandoned pipes. Various groups have helped in the effort including BLM and NDOW employees, volunteers from local Audubon chapters and other NGO’s, field crews with the Great Basin Institute, off-duty fire fighters, and public volunteers.

One such volunteer, Jim Boone, is a retired ecologist and an avid hiker. Once he learned about the issue, Boone began to remove pipes during his hikes.

“It gets to be an obsession,” Boone commented about his involvement. “When I started knocking down markers, I found many dead birds and became appalled by the situation. Now it has become a quest to knock down markers and save birds.” Boone works with Slaughter and others to organize volunteer efforts in Clark County, Nevada.

While most of the dead birds found in the pipes are cavity nesters, many other species and wildlife are impacted. While removing abandoned claims a few weeks ago, Boone discovered 37 dead Ash-throated Flycatchers in one pipe, 66 dead birds in just two pipes, and hundreds of dead birds total. One live bird was released from a pipe while its mate called mournfully from a nearby yucca. “It really shocks you,” he says of what he finds in the pipes. It is not just birds being killed, but mammals like chipmunks and bats, as well as reptiles and insects.

Since the effort in the Southern Nevada District began, workers have knocked down 15,500 abandoned pipes, clearing 95% of the 3.6 million acres. Slaughter estimates there are about 1,000 pipes left to remove. They are on their way to becoming the first BLM district clear of abandoned mining claims, and Slaughter hopes their success will inspire other districts to do the same.

In 2015, The American Bird Conservancy, in collaboration with many other partners, sent a letter urging the BLM and the Forest Service to take action on this issue. In February 2016, the BLM issued a nationwide memorandum entitled “Reducing Preventable Wildlife Mortalities”. The memorandum provides policy for BLM personnel to reduce the likelihood of adverse impacts to wildlife from open, uncapped hollow pipes or tube-like structures by replacing them with wildlife-safe structures or screening the open pipes. This policy change is a major victory in the fight to end preventable and indiscriminate killing of wildlife.

The efforts in Nevada are an example of how a large-scale issue with a straightforward solution can be tackled one step at a time. The next steps include getting more laws in place like those in Nevada, getting more agencies to adopt similar policies to the BLM, and working with all public land management agencies and private citizens to help put these policies into practice.

This Western Pipistrelle bat is one of the many mammals trapped by open pipes (photo courtesy of Jim Boone).

Tenebrionid Beetles and Giant Desert Hairy Scorpion are some of the other species impacted by open pipes (photo courtesy of Jim Boone).

English

English  Español

Español